Something’s on overload – but it’s not collaboration

Something’s on overload – but it’s not collaboration http://mercedgroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/StoneHeads.jpg 788 521 Catherine Shinners Catherine Shinners http://2.gravatar.com/avatar/20369aff7978a3842e7879d0699f8473?s=96&d=mm&r=gRob Cross, Reb Rebele and Adam Grant just published an intriguing article in the Harvard Business Review, decrying Collaborative Overload in the workplace. It seemed to me that much of the challenges and issues they called out did not have much to do with collaboration, per se, but with poor interaction and knowledge management practices, irregular or vague governance and guidance, and haphazard project and team management processes. In my work with organizations and companies, it’s often these kinds of issues that impact productive collaboration.

The big squeeze – knowledge worker contribution amidst changes in nature of work

The knowledge worker of the 21st century is indeed experiencing overload – expectations of continued workforce productivity gains often outpaces the ability of workers to maximize the potential of the use of new technologies while increasing their output. A 2013 Conference Executive Board Report noted unambiguously the high impact of workforce productivity on the bottom line.

“Since 1993, revenue per full-time equivalent (FTE) had grown at a 3.23% compound annual growth rate (CAGR) compared to no growth in revenue per cost of goods sold (COGS; CAGR= 0.16%) and a -0.61% in revenue per invested capital.”

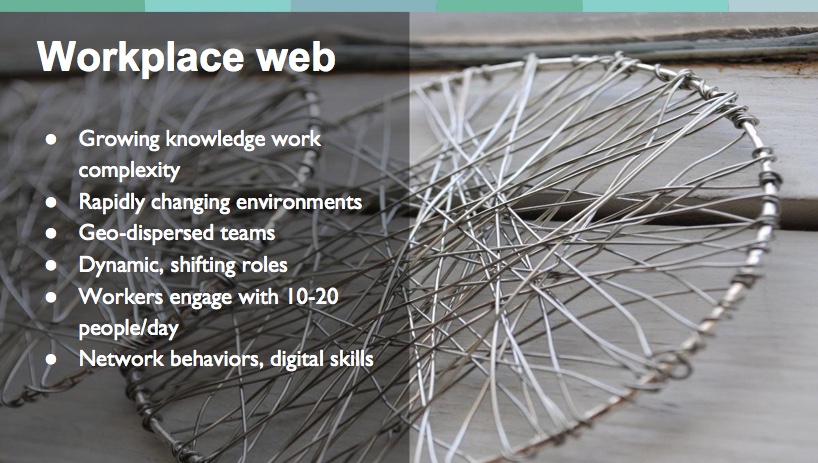

The climate of knowledge work has changed dramatically in the last fifteen years – people are often working on varied. globally dispersed, teams rolling up to multiple reporting structures. They’re collaborating and interacting with customers, prospects and partners online. Workers often must interact with 10-20 people per day to get their job done – a job that is increasingly dependent on information. Add to this day-to-day team, information and interaction complexity are increases in the number and more rapid cadence of organizational shifts and restructuring that knowledge workers must adapt to.

The climate of knowledge work has changed dramatically in the last fifteen years – people are often working on varied. globally dispersed, teams rolling up to multiple reporting structures. They’re collaborating and interacting with customers, prospects and partners online. Workers often must interact with 10-20 people per day to get their job done – a job that is increasingly dependent on information. Add to this day-to-day team, information and interaction complexity are increases in the number and more rapid cadence of organizational shifts and restructuring that knowledge workers must adapt to.As the CEB report notes even with these new work challenges growing, there is also the expectation of a 20% workforce performance improvement among global executives.

Interaction doesn’t equate to collaboration, and some aspects of this article imply as much by focusing the modalities (emails, phone calls, etc) rather than the contexts for collaboration. It’s true that using the wrong tool or modality for the job can be grossly inefficient (email to manage complex workflows, for instance) but some of the overload may be about other issues rather than too much collaboration.

Common work practices gone haywire

Inquiry overload

Aspects of the collaborative overload the article focuses on areas that don’t appear to be collaboration issues (or ad hoc collaboration requests as Cross et al. refer to) but knowledge management work practice gone awry. Many organizations have that ‘go-to’ person who seems to know how to find things quickly or has expertise at their fingertips to share, or seem to be ‘in-the-know’ about what’s going on with organizational shifts and changes. That ‘go-to’ person becomes a human knowledge repository; it’s easier to ‘ask Joe’ rather than seek the information in other ways. Often that person can provide background, insight and context around the information that’s being sought.

There are often three facets to this problem. The first is that people don’t want to bother with searching for the information they need, or the information seems difficult to find, and therefore often turn to that ‘go-to’ person first. Why might information be difficult to locate? The organization’s search technology may not be up to date or well implemented so that search results are incomplete or bring in too much extraneous, irrelevant results Often much information is buried in email chains that’s simply not broadly accessible.

The second challenge is that guidance and governance to the workforce on how to appropriately utilize content management systems is undeveloped or not well-understood. Workplace norms around labeling, tagging, distribution and storing practice are missing. Work practices remain locked into 1990s modalities of using email to coordinate and communicate around complex work processes and as ways to distribute vital business content.

Meeting overload

One of the most intractable challenges in companies today is real-time meeting overload. The ease of access and usability of real-time web meeting tools has helped teams come together easily and quickly to aid in their project work. Unfortunately workers are often in meetings, back to back for 6-10 hours day. Just because people are in meetings, doesn’t mean they’re collaborating. Often they’re multi-tasking since there’s little time to do other work or the meeting content is not applicable to their participation thereby diminishing their productivity elsewhere.

Here are some of the challenges I frequently observe that are not collaboration issues per se

- Meeting norms are weak or lacking – A meeting topic might be established, but no agenda is published in advance to allow people to prepare, evaluate materials, ahead of time. Since people are in back-to-back meetings, there’s no time for people to prepare or publish status or project updates in other, asynchronous formats, so additional meeting time is needed for status updates (for which half the attendees may not find relevant to their portion of the project).

- Collaboration or project norms are weak or lacking – Got a project? Set up a recurring meeting. New projects or new matrix teams often don’t spend a little time at the beginning of joint work to set up simple collaboration norms. Here are some questions that project teams might ask in order to streamline or eliminate meetings.

- What tools should we use to communicate and capture project activities?

- How should we tag and distribute content so it is consistently find-able and people receive timely alerts for new content?

- Who should be in project meetings?

- Do we need to meeting regularly? If so, do we all need to be at every meeting?

- Can we structure the meetings in a way that we use that meeting time to address things that we cannot accomplish as well using other collaboration tools?

Given the over-scheduling of meetings, it’s often difficult to start in a timely manner. If one knowledge worker is in eight 1-hour meetings/day and each meeting started 5-7 minutes late, at the end of the day they would have lost 40-45 minutes of time and perhaps as much as 160-200 minutes/week. Little of this time would be engaged in effective collaboration.

The challenges that Cross et al. call out are less issues with over-collaboration and more about reliance on unproductive default behaviors.

Digital work practice for humans working in networks

Here are some 21st century digital work practices that companies and knowledge workers need to consider to ameliorate overload and support more effective collaboration.

- Part of a work product includes connecting it to and making it findable on a network (link-ability, tagging, connecting to social profiles)

- Part of collaboration means consciously adapting to more transparent ways of working (Working Out Loud)

- Part of team work includes establishing collaborative norms (which tools and modalities for which contexts)

- Part of knowledge worker productivity includes proactively managing flows of information, bringing elements like activity streams and tagged content into their realm of access and awareness.

New digital and social tools can help individuals create conversational spaces where common questions get answered, or discussion around key topics can take place online, and others can see, learn from and repurpose without interrupting the knowledge expert. The conversational aspect of the tools also affords the expert the opportunity to provide context, and there’s a dynamic, sustained thread of their shared expertise. Social collaboration tools also afford the opportunity to create collaborative communities of practice or knowledge networks where expertise can be more broadly and transparently shared and more centrally discovered by seekers.

Many companies are bringing social collaboration environments (enterprise social networks) into the collaborative mix. An important, but frequently underutilized component of enterprise social networks is the rich profile. Similar in concept to a LinkedIn profile, these rich profiles allow a worker to provide information about their background, expertise, interests, their network across the organization, and current work activities or products or blog about their work. Yet this aspect of enterprise social networks are often not uniformly employed to good collaboration effect. Knowledge seekers can use the social profiles in enterprise social networks to identify a variety of individuals with expertise or connections around a topic or information need. An important 21st century work skill is to effectively use and develop networks. Knowledge workers need to develop the practice of searching social profiles for experts as a element of that network skill. Leaders need to put in place work practice change programs to help workers effectively develop and use this skill.

Contexts for collaboration – all collaboration is not equal

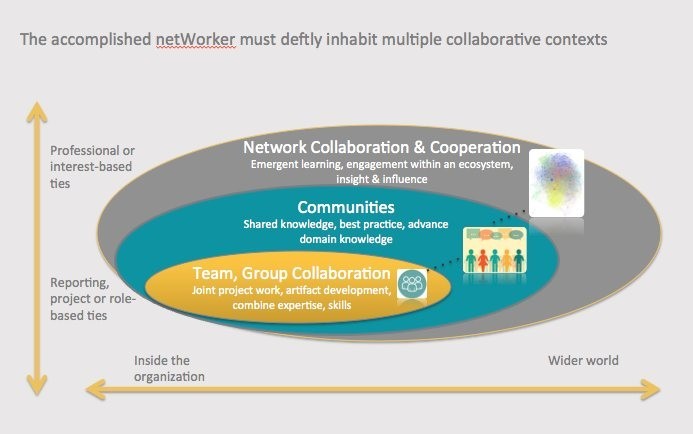

In discussing challenges to collaboration or identifying ways to help individuals and organizations to engage in collaboration more productively, it’s important to be clear about the contexts for collaboration.

Knowledge workers (and this includes leadership) inside organizations must be able to span these contexts to:

- be competent in being able to productively contribute to complex business processes and team projects employing digital and social tools and skills

- be able to develop relationships and participate effectively in knowledge networks to advance their continual learning and skills development and to advance the knowledge capital of the broader organization.

- deftly cultivate, navigate and participate in wider networks for broader insight to emergent and related knowledge fields and access to expertise beyond organizational boundaries.

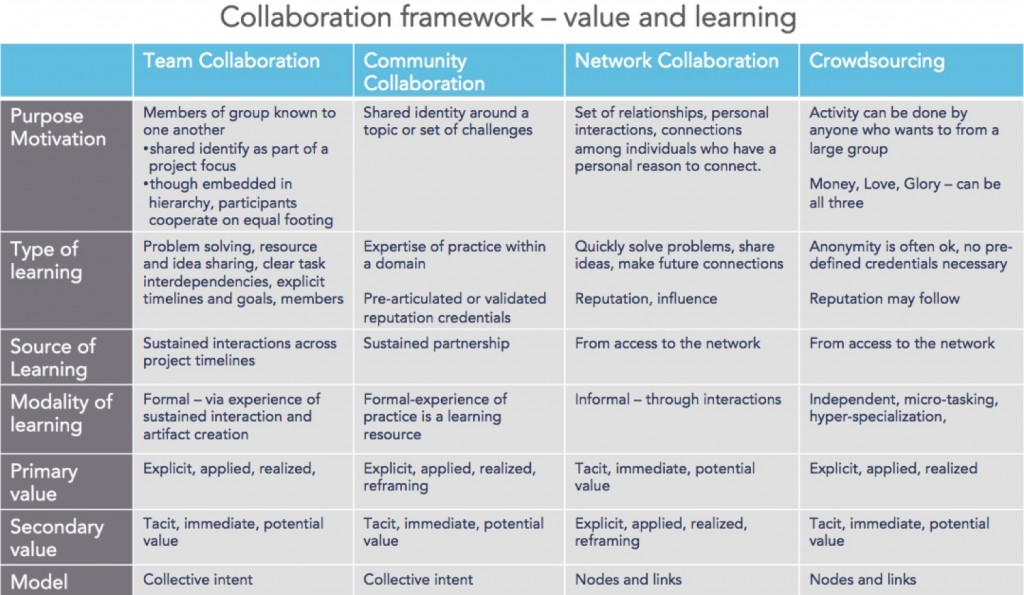

Equally, in evaluating collaboration effectiveness it’s important for knowledge workers, leaders and others to understand that different kinds of collaboration and the inherent value of the collaboration are influenced by the nature of the collaboration context as outlined in the table below.

The purpose and depth of sustained interactions or relationships in team and community collaboration brings specific kinds of value, learning and outcomes. To attain those kinds of value and outcomes requires leadership understanding and support for the right infrastructure, tools, guidance and governance.

Organizational culture and practice can also enable good network collaboration (cooperation really) where knowledge workers and leadership can easily traverse the company as a network, and through less formal or sustained interactions seek the resources of the network to quickly solve problems, share ideas, seek expertise or make connections for future use.

Leaders also need to understand the new social structures of collaboration that include communities and crowdsourcing. I’ve seen internal crowdsourcing used effectively to gain proposals from senior leadership in the organization for new business opportunities against a set of strategic objectives

Engaging in productive collaboration towards business purpose and outcomes is just one of many 21st century skills that knowledge workers and leadership need to master and be able to assess. Knowledge workers are developing these skills as they work more and more in a web-workplace – using digital, cloud and mobile tools to engage and connect and work with global colleagues. Leaders are developing new skills to convene networks and set in motion communities towards business purpose. I co-teach a Social Organization course at Columbia University’s Information and Knowledge Strategy master’s program that focuses on how leaders launch, manage, measure and take in the learnings from communities. These are vital practices and processes for 21st century management practice.

Engaging in productive collaboration towards business purpose and outcomes is just one of many 21st century skills that knowledge workers and leadership need to master and be able to assess. Knowledge workers are developing these skills as they work more and more in a web-workplace – using digital, cloud and mobile tools to engage and connect and work with global colleagues. Leaders are developing new skills to convene networks and set in motion communities towards business purpose. I co-teach a Social Organization course at Columbia University’s Information and Knowledge Strategy master’s program that focuses on how leaders launch, manage, measure and take in the learnings from communities. These are vital practices and processes for 21st century management practice.In future blog posts, I’ll explore more about these skills and practices.

- Posted In:

- Uncategorized